Butterflies, Swans, and Complex Systems Theory

November 3, 2025

Introduction

In our previous post, we walked through our technology stack.

In this post, we explore a concept relevant across economics, neuroscience, biology, mechanics, sustainability, and beyond: complex systems. Think of it as a deep dive into the foundations of complex systems theory.

We define what we mean by complexity, complex systems, and complex adaptive systems, and examine how systems thinking reframes decision-making in an interconnected world. A world that is, itself, a complex system. Whether this is your first encounter with the topic or a return to familiar ground, the goal is to clarify key ideas, connect them across disciplines, and reflect on their implications for how we understand and guide change.

Context

What does it mean to think in systems?

To think in systems is to shift focus from things to relationships between things; from isolated events to the underlying structures that produce them. It means asking not just what is happening, or even why it’s happening, but how different entities interact to create the outcomes we observe. It’s about tracing connections: how A influences B, how B feeds back into A, how C, D, and E are involved, and how those interactions evolve over time. According to this paradigm, you can study A all you want, but you will never fully understand A without understanding how A is related to B, C, D, and E. Furthermore, you can fully understand A, B, C, D, and E individually and would still be missing essential information, because relationships among components matter as much as the components themselves. In short, systems thinking is all about how a whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Now, what do we mean by complexity? And what’s the difference between something that is complex and something that is complicated?

Complicated systems may have many parts, but those parts interact in fixed, deterministic ways. If one component fails, it can be repaired or replaced without altering how the rest of the system functions. A jet engine is complicated: it has many interlocking parts, but its behavior is predictable if you understand the blueprint.

Complex systems, by contrast, involve many interacting parts that influence one another in ways that are nonlinear, adaptive, and often unpredictable. They cannot be disassembled and reassembled without fundamentally changing their behavior. A forest, for example, reorganizes itself in response to shifting conditions; remove or add one element, and the system evolves in a new direction. There is no blueprint.

This distinction matters because many of the systems we depend on – the climate, ecosystems, the human mind and body, economies, and entire societies – are complex. Their behavior emerges from countless interactions across scales, shaped by feedback loops, adaptation, and chance. Small changes can cascade, producing nonlinear, path-dependent, and unpredictable outcomes.

Treating complex systems as though they were complicated ones leads to oversimplified solutions. Of course, we recognize that there are limitations: no model can capture every interaction or feedback in full. The goal is not to eliminate complexity, but to represent it as best we can given our resources and other constraints.

Sustainability depends on this mindset. Social, economic, and environmental systems co-evolve; decisions shape institutions and incentives, which in turn shape the next round of decisions.

Complex Systems Theory & Complex Adaptive Systems

Complex systems theory is a framework for understanding how relationships among parts generate system-level behavior. It is the study of systems defined by nonlinearity, interdependence, and emergence, where global patterns arise from local interactions.

The field draws from dynamical systems theory (which includes chaos theory), statistical physics, information theory, and network science, among others, offering complementary ways to study how complexity arises, organizes, and persists across domains.

For instance, in climate science, dynamical systems models use equations to represent how the atmosphere, oceans, and biosphere co-evolve through feedback loops over time. These models reveal how small perturbations can cascade into large-scale shifts, an example of nonlinear behavior central to complex systems theory.

Understanding complexity also means thinking about how to measure it. Information theory provides one lens: it quantifies how much information a system stores, transmits, and transforms. Highly ordered systems yield little new information, while purely random ones carry too much noise to be meaningful. Complex systems sit between these extremes. They’re structured enough to preserve meaning, yet dynamic enough to generate novelty. This balance, often described as the “edge of chaos,” is where adaptation and learning are most pervasive.

Within this broader framework of complex systems, we have complex adaptive systems, or CAS – systems whose individual components can learn and evolve their behavior over time, thereby altering the system’s overall organization or function. Some examples of CAS include financial markets, the human brain, and ecosystems.

Researchers study complex adaptive systems using computational and mathematical tools that simulate how local interactions give rise to collective behavior.

Among the most common are agent-based models, or ABMs, in which many autonomous agents follow simple rules and interact within an environment. Over time, their interactions generate system-level dynamics – sometimes stable, and sometimes chaotic – that mirror patterns seen in real-world systems. For example, an agent-based model of land use might simulate how farmers, policymakers, and environmental agents interact within a shared landscape. Farmers make planting or irrigation decisions based on local soil conditions, market prices, and climate forecasts; policymakers adjust incentives or regulations in response to observed land degradation; ecosystems respond through changes in soil fertility, water availability, and vegetation cover. These roles and feedbacks interact across scales, producing emergent regional patterns that might include deforestation, water scarcity, and ecosystem recovery, as well as a range of other possibilities.

Another key approach is network modeling, which represents systems as nodes and links to reveal how patterns of connection shape system behavior. Network models reveal how connectivity (the number and strength of links), clustering (the degree to which nodes form tightly knit groups), and centrality (the relative influence or importance of nodes) shape processes such as diffusion (of, say, information, energy, or disease), robustness (the system’s ability to maintain overall function when some nodes or connections fail), and vulnerability (its susceptibility to cascades or large-scale breakdowns).

What Characterizes Complex Adaptive Systems?

Though definitions vary, complex adaptive systems share several widely recognized characteristics:

Multiple interacting components

Many interconnected elements interact in ways that are dynamic (the rules governing their behaviors and relationships evolve over time), decentralized (no single agent governs the system’s overall behavior; coordination emerges from local interactions), and context-dependent (each interaction’s outcome depends on the current state of other components and environmental conditions). Connections can span both space and time, linking processes that unfold at different scales and over varying temporal horizons.

Adaptation, co-evolution, and self-organization

Individual components continually adjust their behavior in response to feedback from one another and from their environment. These local adaptations accumulate, leading to co-evolution, which is when one agent’s change alters the conditions and incentives of others, prompting further adaptation in return. This recursive interplay allows the system to reorganize and evolve without any central control.

Through these decentralized adjustments, systems can exhibit self-organization: the spontaneous emergence of coherent structure or function from local interactions. Order arises not because any central entity designs it, but because feedback processes reinforce certain patterns over time. In ecological systems, for instance, vegetation can self-organize into patchy mosaics that regulate water and nutrient flows.

This interplay drives systems-level innovation and diversity, enabling new patterns, strategies, and structures to emerge over time.

Emergent properties

At the systems level, new patterns and behaviors arise, and these new patterns and behaviors cannot be explained by examining individual components or by scaling up the rules that govern the individual components locally.

In his famous 1972 essay More Is Different, physicist Philip W. Anderson argued that as systems increase in complexity, each new level gives rise to its own organizing principles: principles that are not reducible to those of the level below. Emergent properties are therefore not secondary or derivative; they are as fundamental to understanding systems as the micro-level mechanisms that produce them. In other words, even if we understood every single thing there was to know about atoms – including how all atoms relate to and interact with one another – we would still not understand something like molecular biology, because the behavior of molecules depends on new patterns of organization, constraints, and interactions that arise only when atoms combine into higher-order structures. Another example: understanding neuroscience is not enough to understand consciousness, because consciousness emerges from but is not reducible to the electrochemical activity of neurons. The coordinated dynamics of perception, memory, and self-awareness arise only when billions of neurons interact in complex networks.

The graphic below illustrates various hierarchical levels of organization:

Note that self-organization and emergence are distinct concepts. Self-organization describes how order arises spontaneously from local interactions without central control – for instance, the formation of spiral patterns in hurricanes or convection cells in heated fluids, both of which arise from countless local interactions governed by simple physical rules. Emergence, by contrast, refers to the appearance of new properties or behaviors at higher levels of organization that cannot be predicted from lower-level rules. For example, consciousness emerges from neural activity, or market dynamics emerge from countless individual buying and selling decisions; these phenomena cannot be reduced to the properties of neurons or traders themselves, or the rules governing their interactions.

Nonlinearity and feedback

Interactions are nonlinear. Reinforcing feedback loops amplify small perturbations in a system, sometimes driving a system toward a tipping point: a critical threshold where gradual change suddenly triggers a large, often irreversible “regime shift” where an entire system changes into a new state. Balancing feedback loops, by contrast, counteract change and stabilize the system, maintaining equilibrium or homeostasis over time.

A few paragraphs earlier, we discussed the ways in which adaptation and co-evolution enable systems to innovate and diversify. However, the same adaptive flexibility that fosters innovation and diversity can also lead to instability through reinforcing feedback loops, potentially leading systems toward their tipping points and into regime shifts. These regime shifts are seen in coral reef collapses, climate feedback loops, and financial crises. One well-known example is the melting of polar ice caps. The bright white of the ice reflects solar radiation back into the atmosphere. As ice melts, it exposes darker ocean or land surfaces that absorb more solar radiation, further accelerating warming and causing more ice to melt, exposing more darker surfaces, leading more ice to melt. A classic reinforcing feedback loop. This process not only amplifies global warming but is also pushing the Earth system toward a tipping point, where it will continue losing ice even without further external forcing. That means that polar ice loss will become self-sustaining even if emissions are reduced. One challenge is that tipping points are hard to foresee because systems can appear stable until incremental change accumulates and abruptly triggers a large, irreversible shift.

These dynamics also explain the prevalence of what statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb called Black Swan events: rare, high-impact occurrences that lie outside standard predictive models.

In complex systems, such events emerge from hidden interdependencies, nonlinear amplification, and feedback effects that conventional linear models fail to capture. As discussed earlier, because small changes can cascade through networks in unpredictable ways, systems can appear stable for long periods and then abruptly reorganize when a critical threshold is crossed.

Black Swans, therefore, are not just statistical outliers but structural consequences of complexity. And they need to be accounted for as much as is possible in complex systems models.

Balancing feedback loops play a vital role in maintaining coherence and continuity within a system. They regulate fluctuations, dampen shocks, and keep variables within functional bounds. These processes are often described as homeostasis in biological systems or governance in social ones. By counteracting excessive change, stabilizing loops enable persistence, coordination, and reliability, allowing systems to retain identity and function even as their environments fluctuate.

It is important to note that reinforcing feedback loops are often beneficial, and that balancing feedback loops can be harmful. It all depends on the context.

Reinforcing loops can produce self-sustaining progress by amplifying desirable changes such as the diffusion of a positive technological innovation, the strengthening of cooperative norms within social groups, or the acceleration of learning within an ecosystem. In these cases, reinforcement enhances adaptive capacity rather than instability, enabling the system to evolve toward greater functionality.

Meanwhile, balancing feedback loops can sometimes entrench undesirable structures or behaviors. This leads to lock-in, when balancing loops trap the system in a suboptimal state, making transformation difficult even when better alternatives exist. Moreover, while “stable,” this state does not inherently protect a system from external disruption.

Resilience

The goal, then, is not simply to blindly suppress reinforcing feedback loops or maximize balancing feedback loops, but to understand the entire system and the specific feedback loops at play, and to bolster those that strengthen system resilience and intervene in those that undermine system resilience.

Resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb shocks, adapt, and reorganize without losing its essential structure or function. Resilient systems maintain a dynamic balance between change and stability. Systems with healthy connectivity and diversity tend to be more resilient because they can share resources, distribute stress, and adapt through multiple pathways. But when components become overly interdependent or homogeneous, a disturbance in one part can propagate rapidly through the whole network, leading to cascading failure or collapse.

Resilience is not static; it changes over time as systems learn, reorganize, and adapt to new conditions. A resilient system does not merely return to a prior state after disturbance; it may reorganize into a new configuration that preserves its core function while altering its structure. In this sense, resilience is closely linked to adaptive capacity and transformability: the ability to evolve in response to shocks beyond simply withstanding them.

In CAS, resilience often depends on multiple feedback pathways, diversity, redundancy, and modular organization.

Multiple feedback pathways create alternative routes of regulation and adaptation, so the system is not reliant on any single control loop.

Diversity (in species, ideas, institutions, or technologies) serves a similar purpose by providing alternative responses when dominant pathways break down.

Redundancy, meanwhile, refers to functional overlap: when multiple components can perform similar roles, one can compensate if another fails.

Modular organization means that components are semi-independent – clustered into subunits that interact but can contain disturbances within themselves – so shocks in one part do not immediately spread across the whole system. In network theory, such modular or “small-world” structures balance local clustering with a few long-range connections, enabling both robustness and efficient information flow: disturbances are largely contained within modules, while adaptive coordination across the network remains possible.

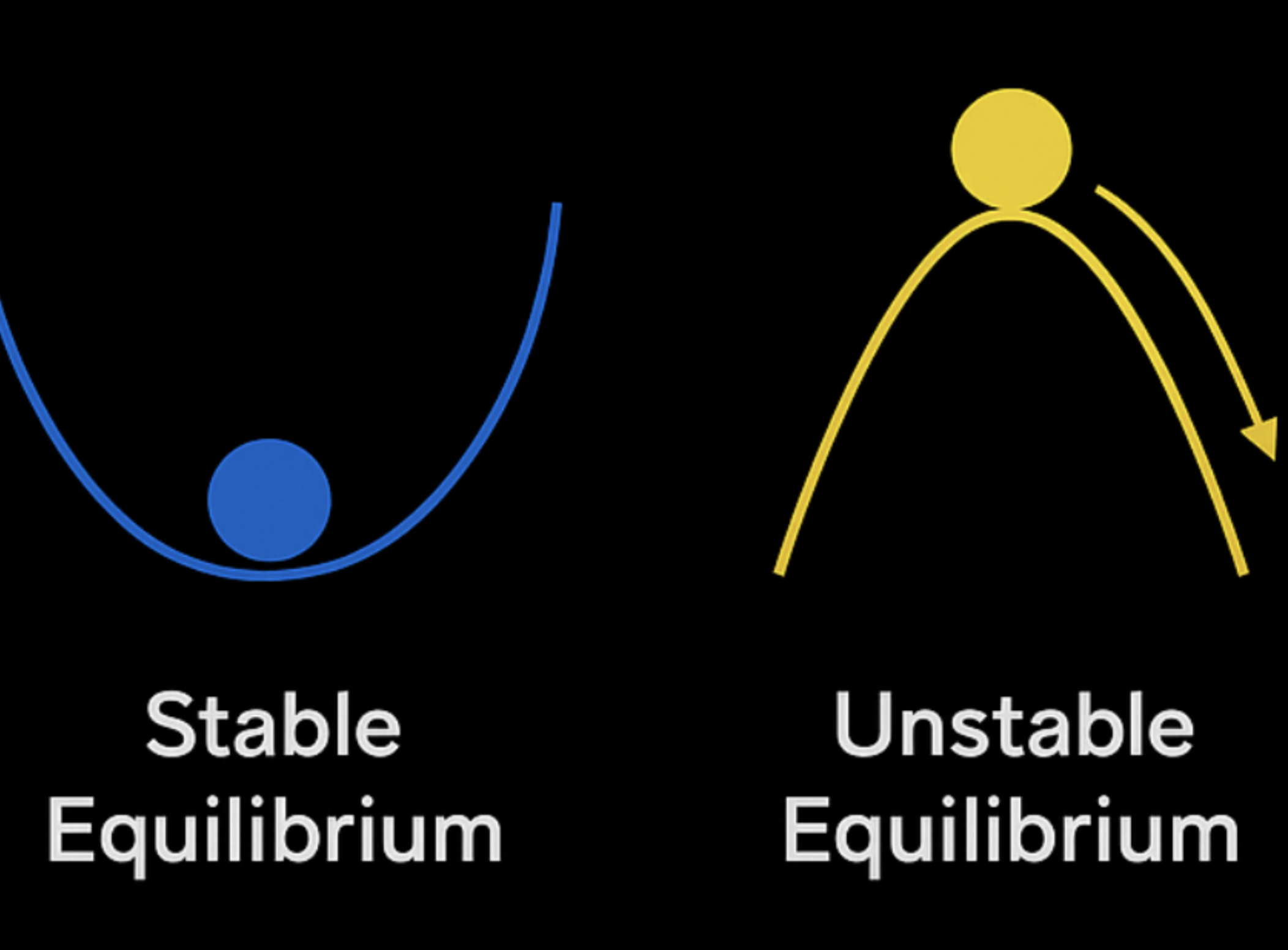

Stable vs Unstable Equilibria: Marble on a Hill

A system can be balanced but not resilient. We alluded to this earlier, when we explained that balancing feedback loops, even if leading to a “stable” system, are not necessarily protected from external disruptions.

Okay, at this point, we have to admit – we’ve been using the word “stable” a little loosely so far. We’ve used it to describe complex adaptive systems that seem balanced and are not lurching toward a tipping point. But in systems theory, stability has a more specific meaning, and to understand it, we need to introduce the concept of equilibrium.

An equilibrium is a state in which the forces or feedbacks within a system (keyword: within) are balanced. But not all equilibria are alike. Specifically, they differ in how they respond to external perturbations. Some equilibria are stable, meaning that if the system is nudged slightly from the outside, feedbacks will act to restore it to equilibrium. Other equilibria are unstable: a small external disturbance pushes the system further away, triggering reinforcing feedbacks that move it toward a different state.

Imagine two marbles: one resting in a valley, and one resting atop a hill.

The marble resting in a valley represents a stable equilibrium. If nudged, it rolls uphill a little bit, then rolls back toward the bottom of the valley. A marble perched at the top of a hill represents an unstable equilibrium: it’s at rest, but a tiny push sends it rolling irreversibly into the valley.

Understanding this distinction is important because a system can be balanced at equilibrium (internally balanced) yet not resilient (unable to absorb large or external disturbances) if the equilibrium is unstable.

This analogy is also helpful when thinking about how and when to intervene in systems, especially under uncertainty. Before “nudging a marble,” we must ask whether the marble will return to equilibrium after a disturbance, or whether the disturbance could trigger an irreversible shift into a new state. Acting responsibly, then, requires understanding what feedbacks that push might activate and what trajectories it could set in motion.

Types of Uncertainty

As we’ve discussed, complex systems are inherently uncertain. This raises a question: What does “uncertainty” actually mean?

There are two primary types of uncertainty – one tied to randomness, and the other to incomplete knowledge.

Aleatory uncertainty refers to inherent variability or noise – randomness that remains even when the governing rules of a system are known. For example, weather models include stochastic fluctuations in atmospheric motion that cannot be predicted precisely, even with perfect equations. This kind of uncertainty is irreducible: it reflects the system’s intrinsic randomness.

Epistemic uncertainty, on the other hand, arises from limits to what we know about the system itself. We may not know all the relevant variables, parameters, or feedback structures; our models may simplify or omit mechanisms that matter. This type of uncertainty is reducible in principle, because it stems from incomplete knowledge rather than randomness. But in practice, it can be difficult to model.

A related distinction, often attributed to economist Frank Knight, is between risk and uncertainty:

Risk corresponds to known unknowns – situations where possible outcomes are known and probabilities can be assigned (for example, rolling a die or estimating rainfall variability).

Uncertainty, in the stricter sense, refers to unknown unknowns – situations where we do not even know all the possible outcomes or mechanisms, much less their probabilities.

Aleatory uncertainty aligns with risk: we can describe inherent variability statistically. Epistemic uncertainty aligns with true uncertainty: our ignorance prevents probabilistic specification. This distinction shapes how we think about uncertainty. Aleatory and epistemic uncertainty require different tools. The former is best captured through statistical methods that describe randomness, while the latter calls for frameworks that represent incomplete or evolving knowledge.

For now, we’re simply introducing uncertainty as a key idea within complex adaptive systems (and in our next blog post, we’ll dig deeper into how uncertainty can be modeled). With that, we’ll continue our conversation about systems thinking and how it shapes decision-making.

How Systems Thinking Shapes Decision-Making

Seeing the world as a complex adaptive system changes how we think about decision-making. It challenges the notion that we can fully predict or control outcomes, instead emphasizing the importance of understanding relationships, feedback, and context. In complex systems, effects are rarely linear – small actions can have outsized consequences, while large interventions can fail to move the system at all. The goal, then, is not control but identifying where small, well-informed interventions can produce meaningful, lasting effects. To put it differently: identifying where you’ll get the most bang for your buck.

In Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System (1999), systems theorist Donella Meadows described these points of interventions as leverage points: places within a system where a modest adjustment can generate major shifts in behavior. Some leverage points lie near the surface, such as changing parameters or resource flows. Others are deeper, involving shifts in information structures, goals, or paradigms. The deeper the leverage point, the more profound and enduring the potential change.

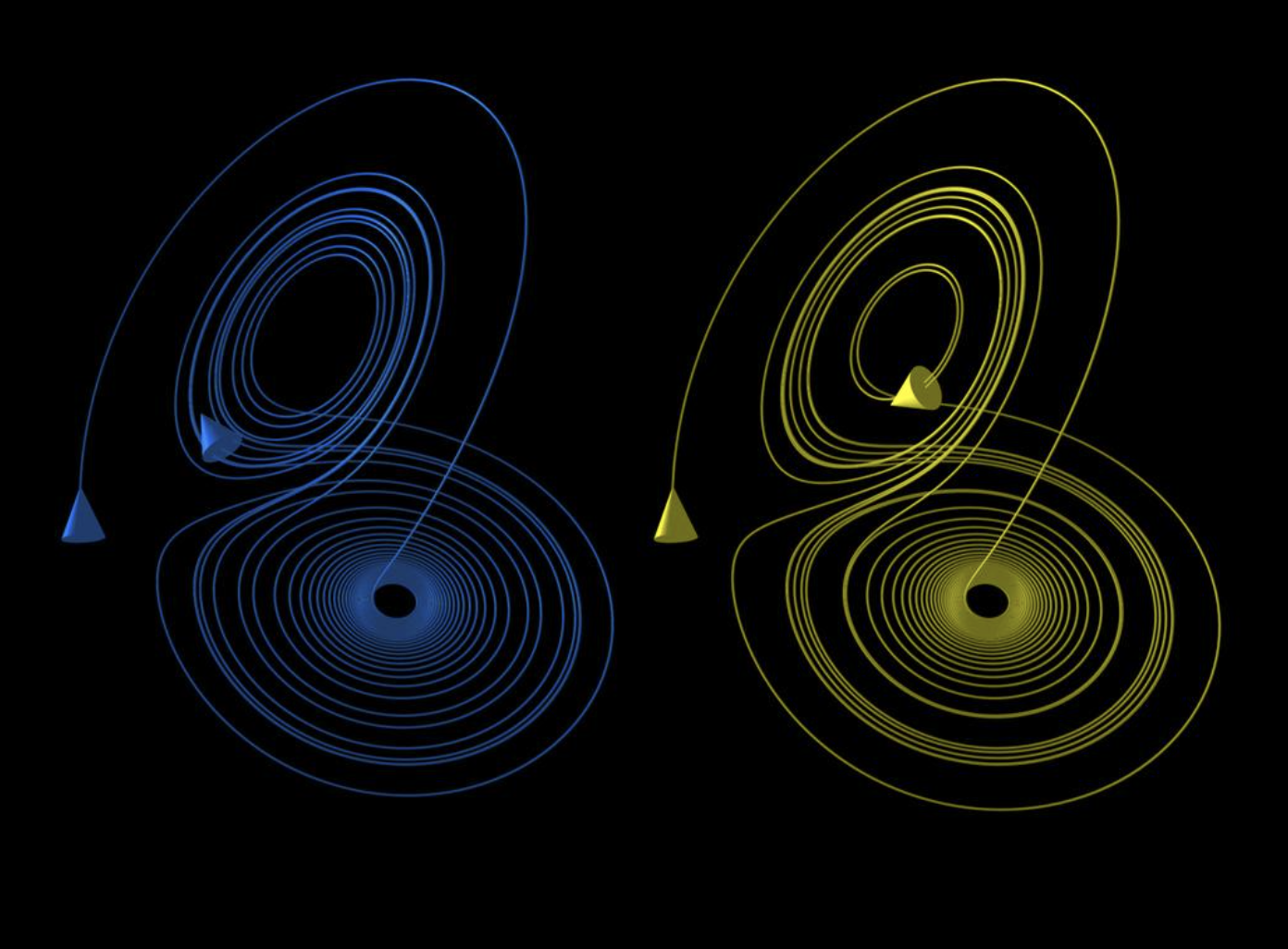

A recurring (and very important) lesson from complex systems research is the limit of prediction. As illustrated by the butterfly effect, a principle of chaos theory, even minute changes in a system’s initial conditions can lead to vastly divergent outcomes. And we cannot measure initial conditions with infinite accuracy due to physical limitations of measuring tools, which makes precise forecasting impossible beyond a certain horizon. In the image below, two trajectories evolve from nearly identical starting points within the Lorenz attractor, a classic example of a chaotic system. Despite beginning almost the same, their paths quickly diverge, spiraling into entirely different regions of the state space.

Because exact prediction is impossible, the aim shifts from forecasting specific outcomes to understanding the range of possible system behaviors (their probabilities, sensitivities, and risks) and building decision processes that learn and adapt as the system itself evolves.

Thinking in systems therefore also demands a level of humility. Working within complex systems calls for experimentation, learning, iteration, and continual adaptation. To reiterate: strategies must be built to evolve as the system itself evolves. Adaptive management is an idea that centers around treating policies and strategies as experiments, adjusting them as feedback reveals what works and what doesn’t. This approach replaces static planning with iterative learning, where decision-makers refine their understanding of the system as it responds. In practice, this means embedding monitoring, feedback, and revision loops directly into governance, policy design, organizational strategy, and action plans.

Recognizing complexity does not make decisions simpler, but it does make them wiser and more context-aware. In a sense, the complexity of the world sets the standard for how decision frameworks should be built. They should be built to adequately reflect the complexity of the systems they serve. The methods behind decision intelligence frameworks for complex systems should be…well…complex.

~The GaiaVerse Team

Up Next

In our next blog post, we’ll take a closer look at how uncertainty is modeled in complex systems, looking at the conditions under which probability theory and possibility theory are best applied.